Walking around Liberty Aviation Museum, you never know who you may run into. Below are the amazing stories of just a few of our special visitors that are no longer with us...

Edward Stevens

Today Liberty Aviation Museum had a special guest, Edward Stevens, who was a Tri-Motor pilot and co-pilot with Island Airlines in 1956. Mr. Stevens graced us with memories and stories and photos from his time at Port Clinton.

Before flying with Island Airlines, Stevens was a map maker in the Army, and worked as a crop duster. Later he specialized in photogrammetry (you may want to look it up on Ed's website, www.edstevens.net).

Steven's currently works two days a week as a tour guide at NASA Glenn Research Lab. Edward passed on September 16, 2001.

Guests at Liberty Aviation Museum are often part of living history, and add their stories to the experience.

Willis J. Lodge

During the Labor Day (2013) weekend festivities, we were visited by numerous WWII Veterans and their families. One visiting vet particularly stood out when he started to explore Charlie Cartledge’s beautifully restored TBM Avenger in the hangar bay.

Willis J. Lodge of Bellevue, Ohio, had been a rear gunner on a very similar TBM. Willis was a part or the three man crew that flew TBMs in VT-34 while stationed on the USS Monterey CVL 26 in 1945. Willis survived two crashes in a TBM!

The first one occurred on July 10, 1945 in Tokyo Bay. His squadron of 9 TBMs had been ordered to take out the Atsugi Radio/Control buildings outside of Tokyo. They were also told many of them would not be coming back.

Willis’s aircraft survived the bomb run, but ditched into Tokyo Bay. “It was a perfect water landing” stated Willis. “The Pilot was knocked unconscious by the impact. We couldn’t get the bomb bay doors closed so the Radioman was almost knocked out from the heavy observation window which blew into the compartment during the impact.

Willis pulled the emergency life raft out and got both Pilot and Radioman into the raft before the aircraft sank – all within 52 seconds of the impact. They were within a half mile of the beach. He remembers a woman hanging her laundry up, while a dog was barking and men began taking pot shots at them. Luckily, the USS Gabalin (submarine) broke the surface and they were rescued. Later he found out that only 3 of the original 9 TBMs returned to the decks of the Monterey.

Willis’s second crash occurred while returning to land on the carrier. They had taken some ground fire. The radio equipment was on fire, and they were pitching it out the rear entry door. The hydraulics were shot, the crew was able to get the landing gear down, but did not know one of the tires was destroyed. When they hit the deck the aircraft skidded to the port side of the carrier and was hanging precariously over the edge of the deck. Had it not been for the 12 flight deck crewmembers who threw their body weight onto the TBM the aircraft would have pitched over the side of the carrier.

Willis’s other stories included knowing George H. Bush while they were both briefly stationed at Floyd Bennett Field. Gerald Ford was a Gunnery Officer stationed on the USS Monterey at the same time Willis’s squadron was aboard. Practically all their missions involved using bombs. Only once did they carry a Torpedo. Willis passed on July 16th, 2014, shortly before the TBM Avenger reunion at the Liberty Aviation Museum.

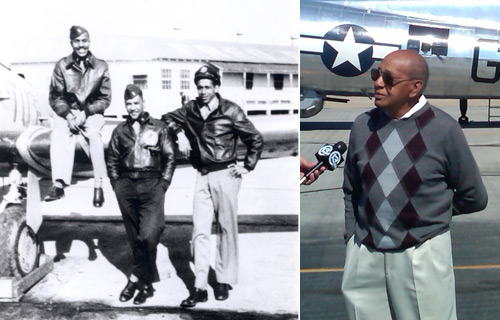

Dr. Harold Brown

This man’s career began, as an 18 year old from Minnesota who joined the U.S. Army in 1942 and became one of the “Tuskegee Airmen” in the 322nd Fighter Group as a member of the U.S. Army Air Corps’ first units of African-American Combat Pilots. Earning his wings following his 19th Birthday he returned to his hometown … receiving a “hero’s welcome”. “Being a Black Officer was just unheard of and a Pilot on top of that…” (Think about this - the Wright Bros’ First Flight had only been 40 years before) “…we knew we were a very special select group of people”.

Harold and his buddies did not know they’d be making history. “All I wanted to do was fly airplanes”. On Harold’s 12th mission he fought against the new Me 262 Jet Fighters, and crash landed his P-51 after running low on fuel. On his 30th mission his aircraft was damaged from the explosion of his target, and he was forced to bail out, and was taken as a Prisoner of War. Harold returned home in June of 1945 at the age of 20. “I’d been through all of that, and wasn’t even old enough to vote”.

Harold remained in the service of the U.S. Air Force for 23 years retiring as a Lt. Colonel. He earned a Master’s Degree and Doctorate from The Ohio State University and spent 22 years at Columbus State College and Served as Vice President of Academic Affairs for 13 years. Dr. Harold Brown received the Max J. Lerner Distinguished Governmental Service Award from the Ohio Association of Career College and Schools (OACCS) a statewide association of voluntary membership for nonpublic, postsecondary private schools and colleges. Dr Brown notes that after 23 years of service in the U.S. Air Force and another 22 years in fields of Business and Academics most people just want to talk about his experience in the war, and points out “…that most people want to hear about my time as a young kid who couldn’t even vote”. Harold passed on January 12th, 2023. A memorial and sculpture are currently in the works. The Liberty Aviation Museum has also named their WWII PT-17 Stearman Biplane "Harold's Dream" in honor of Harold.

Art Kosino

Art Kosino was in the 8th Air Force, 305 Bomb Group. On Art’s 27th mission they were headed to Poland with Phosphorous Bombs when they were jumped by ME-109s and FW-190s. A 20mm round set off the phosphorous bombs, and one of the bomb bay doors jammed so that they could not jettison the load. The bombardier climbed in to the bay and kicked open the jammed door so they could release the load. The aircraft was still on fire, and the crew rear of the bomb bay had no choice -- the skipper ordered them to bail out. Art had had no parachute training, but when the plane was on fire, he didn’t need any; he just jumped out the rear door. The Pilot decided to take the wounded B-17 back to base because the radioman’s parachute had been destroyed by another 20mm round. Art told us that both the Pilot and Bombardier received medals for their valor that day.

Art Kosino, landed backwards and rolled onto his back, and he believes had he come down facing forward, he would have braced his legs, and probably broken them. The next thing he knew he was staring down the double barrel of a farmer’s shotgun. The farmer told him, in broken English, “Fur u, de War ist Uber!” Pretty soon he had the seat of honor in a BMW motorcycle sidecar with a soldier riding the jump seat with his machine pistol trained to Art's head. Finding our BMW motorcycle and sidecar brought back a lot of these long forgotten memories. Art Kosino spent 13 months in Stalag 17 B, and was liberated by Patton’s 3rd Army in the middle of the woods, when the German’s tried moving their guest to another location. Art Kosino passed on December 1, 2015.

Jerry Rasmussen

Ball Turret Gunner in a B-17

303rd Bomb Group

8th Air Force

15 Missions

Mark Pownall

A Short Autobiography (WWII)

"After graduating from Toledo Scott H.S. in June 1943, I enlisted in the Army Air Force, since I had qualified for Aviation Cadet Training while a senior in high school. After a few weeks, I received orders to report to Miami Beach for basic training as a private in the Army.

"Basic training lasted longer than usual due to government snafus. In November 1943 I was sent to Butler University in Indianapolis, which was a College Training Detachment. There I attended college for four months as an aviation student.

"In March 1944 I was shipped to the San Antonio Cadet Center for Classification, which involved qualification testing for the Aviation Cadet program. Passing grades would determine the next course of training, either pilot, navigator, or bombardier. The tests, mental, physical, and coordination, each took one day to complete. Fortunately I passed and qualified for all three. I chose pilot training and was enrolled into Class 45-A.

"The first phase was Pre-Flight School just across the road from Classification. Presently it is called Lackland AFB. After nine weeks of ground school training, I was shipped in June 1944 to Primary Flight School at Jones Field in Bonham, Texas.

"Primary involved learning to fly in a PT-19 Fairchild trainer. An open cockpit low wing monoplane, it was fun to fly, aerobatics, helmet and goggles, and all. After nine weeks I was sent to Basic Flight School at Perrin AFB in Sherman, Texas. Turned out to be only thirty miles west of Bonham.

"There I flew a BT-13 Vultee Valiant. Having a greenhouse type cockpit, it was a lot more powerful than the PT-19 and equipped, among other things, with flight instruments, radio, and night flying capabilities. This turned out to be the toughest training phase and, at least, a third of the class washed out. Fortunately I got through it and was sent on to Advanced in December, 1944. Just prior to leaving, I was given a choice of either single engine or multi-engine training. Not crazy about aerobatics and desiring more than one engine, I chose the latter.

"Advanced turned out to be in B-25s at Pampa AFB in Pampa, Texas. The B-25 Mitchell, a medium tactical bomber, was a joy to fly. My favorite of all. Didn't take long to solo, either. The training was intense but the pressure was less. They got us this far and they didn't want to lose us. In March 1945 I graduated and won my wings and a commission, and immediately left for Transition training at Hendricks Field in Selbring, Florida to fly B-17 Flying Fortresses.

"The four engine Fortress, as everyone knows, was quite an airplane. Big, but easy to fly.

"Close to completion of Transition, and the eventual destination being the 8th Air Force in England, V-E Day occurred (May 8, 1945) and those plans changed. I was on the base when the news broke. Germany surrendered. Our celebration was somewhat muted knowing Japan was next, and it woldn't be easy. Later that day we went to Selbring and joined their celebration.

"Our training continued, however, and in early July 1945 I was transferred to Lowry AFB in Denver, Colorado to fly B-29s. This phase was to involve training for the invasion of Japan. The Super Fortress was quite a change from the B-17. Larger, more powerful, pressurized, with advanced technology, it was like moving up from a Chevrolet to a Cadillac. Didn't get in much time due to the war ending on August 14, 1945 (V-J Day.) The B-29s we had were all grounded that day and future flight time was in other aircraft, mostly B-25s. That was ironic.

"Like Hendricks, I again was on the base then the surrender news was received. A group of us immediately left for downtown Denver to join what was becoming joyously wild, but first we all felt that it was important to stop at church. Downtown it was crazy, everyone hugging each other and military swapping ties with civilians, climbing on top of streetcars and completely blocking off traffic.

"Pretty much left to ourselves, postwar activity at Lowry basically involved waiting for future assignments, such as foreign occupation duty, flying troops home, among other rumors. Other than getting my commercial pilot's license at Stapleton Airport, nothing much happened for two months when the decision was made to offer us discharges or reserve status. I chose reserve status, which involved separation from the Air Force, not a discharge. Separation occurred in October 1945 at Sioux Falls, South Dakota

"I arrived home in Toledo shortly after. My reserve status lasted until May 1958 when I was discharged. I left as a 1st Lieutenant."

Reflections

"The older I get the more it boggles my mind at what I did as a young man (make that “boy”) less than two years out of high school (1943.)

"Everyone at that time was eager to serve their country in the best way possible. Since flying was my strongest interest, the Army Air Force was my first choice. Looking back, I wouldn’t take anything for the training I received. On the other hand, they couldn't pay me enough to repeat it.

"I felt I did my best to serve Uncle Same in WWII, but the greatest result for me was meeting my future wife. Ah, but that's another story." Mark Pownall passed on November 30th, 2018

...Do you have a story to share? Stop in and talk to us!